Summary

The character of the race from Melbourne to Osaka was discussed from a variety of angles. In order to provide larger opportunities for different types of yachts to enter and to make it easy to understand for the general public at large, a decision was made to have a scratch race without handicaps based on IOR or other regulations. In a scratch race, as difference in the performance of individual yachts is obvious, hardly any restrictions on the hull and rigging were added so that participants could be inventive.

In recent years, shorthanded races have become popular. This race was to traverse the Pacific longitudinally not horizontally and the race course set through areas with obstacles such as coral reefs. For this reason, we made it double-handed so that at least one person could be on watch at all times. Short-handed sailing requires easy handling of the yacht as well. From this point of view too, it was necessary to put no restrictions on the hull and rigging. In a scratch race, if the gaps in the capability of yachts are too large, interest in the race would decrease and the time interval between the first finish and the last finish would be too long. Therefore, the length of the yacht was set to be between 10 meters and 16 meters and boats were further divided into Class A and Class B. Because many yachts in Japan measure up to 12 meters in length, we set 12 meter as the dividing line, However, this enlarged the range of length in Class A (12-16 meters) compared to Class B (10-12 meters).

In the South Pacific, a large number of yachts visit various islands and enjoy cruising and so to provide an opportunity for these yachts to enter this race, we established a Cruising Division. Since cruisers place an emphasis on comfort, they inevitably have a larger weight and tend to be slower than lighter racing yachts. By separating the heavier yachts, which otherwise had little chance of winning from lighter racing yachts, we encouraged the participation of cruising crews and presented a new approach to conventional yacht racing. Since the race was to be a double-handed race through the areas with many coral reefs, a great deal of attention had to be paid to safety measures. To begin with, we required that crew members have a certain level of experience in shorthanded sailing. With regards to the yachts, we decided to apply IOR Special Regulations Category 0 which is the strictest set of rules for ocean races. These regulations for example, require that the vessel have an emergency position indicating radio beacon (EPIRB). In order to have reliable communication during an emergency, we required not only adequate radio equipment but also a position indicating system called ARGOS, which we will mention later, in order to confirm each yacht’s position. This information was passed regularly to the rescue organizations of the countries concerned.

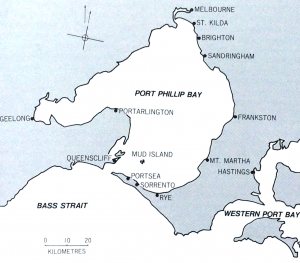

From January to March, cyclones often develop in the area east of Australia and in the area near the South Pacific islands in the Northern hemisphere, typhoons begin to develop around May. Therefore, it was decided to start from Melbourne in late March when cyclones are less likely to develop and to have them pass through the dangerous area before the typhoon season begins. Along the course, many islands are scattering around New Guinea with high density. However, we did not put any restrictions on passages and so yachts could take any course they wish. With regards to the entrance to Osaka Bay, we did designate a passage through Yura Seto. This restriction was set not only to ensure safety but also to enable the race organizers to check the yachts as they enter Osaka Bay. This race which connected the two sister ports and cities of Melbourne and Osaka was to start from Port Melbourne and finish at Port of Osaka. As seen in the map below, the heads of Port Phillip Bay are quite narrow and the current is very fast. Therefore we had to set the starting time so that yachts could sail with the current during daylight hours. To do this, the race was divided into the First Leg stretching from Port Melbourne to Rye and the Second Leg from Portsea to Osaka. In this way, all the yachts could pass through the heads en-masse at the most suitable time.

ARGOS System

The ARGOS system is a system originally designed for automatically collecting meteorological information such as air and water temperature. When the device on the sea surface that measures such data receives inquiring signal from a satellite, it transmits the numerical data to the satellite. The satellite stores the data and sends it when it passes over the key station located in Alaska. The station analyzes this data and confirms the position of the device on the water. This position is extremely accurate. Moreover, since the system covers the entire earth, it’s gradually being used more for obtaining accurate positions rather than for getting meteorological data. So far, this system has been used for a variety of purposes like placing buoys with transmitters on sea currents to study how they flow or attaching transmitters to dolphins to follow their movement.

For yacht racing, this system has been used in single-handed races in the Atlantic. Since the signals emitted by the transmitter on a yacht are analyzed at the land station, the yacht cannot receive the data regarding its own position. When a special pin the transmitter is pulled out, an emergency signal is transmitted. However, since this emergency signal must first be received by the satellite when it passes over the yacht, and then be dropped to the key station when the satellite passes over it, there is normally a delay of two to five hours before the emergency is recognized. This is unavoidable. The first information on “Castaway Fiji” incident that is to be discussed later was obtained through ARGOS system and additional pieces of information were provided which proved highly useful for the rescue operation.

Signals from the yachts are received at one time in Alaska for analysis and then transferred to the computer center in Toulouse, France. There, the information is sorted out in terms of position, yacht speed, heading direction, distance covered, etc., and is stored in the computer memory. The race headquarters in Osaka and Melbourne can connect with the computer in Toulouse through international communication lines to have their own computer output the data. When an emergency signal is received and the emergency is confirmed, the rescue organizations of the countries involved are notified immediately through the French authority that informs the same to Osaka by telex.

Application for Entry

The outline of the race, which had been under discussion since January 1984, was more or less completed by October and the plan for the race was announced. Then in January 1985, the official announcement was made and the Notice of the Race was sent to yacht clubs and yachting magazines throughout the world. In March, Mr. and Mrs. Niwa applied as entry No.1. After that, although there were inquiries about the race, we had only few applications. Even at the end of 1985, there were only about 10 entries. However, due to the efforts by the people and parties concerned, the race became well-known by the summer of 1986 and the number of entries began to increase. It became clear that the total would definitely exceed the expected number by a large margin, which surprised the organizers. By the end of 1986, the deadline for entry, the number came to 97.

On the other hand, we had withdrawals and this made the net total 90 at the closure of entries. Cancellations continued even after the closure and there were 27 yachts that expressed withdrawal by the time of the Skipper’s Meeting. Reasons for cancellations varied. Some could not find sponsorship, while others could not make the necessary preparation in time. There was one heart-warming withdrawal where a skipper’s wife who’d planned to go on the race became pregnant. On the other hand, there were also unfortunate cases like the yacht dismasted in Bass Strait during the delivery cruise to Melbourne.

Safety Inspection

This race introduced IOR Special Regulations Category 0 which is the strictest of the safety regulations for ocean races and inspections had to be carried out to check whether the participating yachts complied with these regulations. However with so many entries, all of the yachts could not be moored at Sandringham Yacht Club, the host club. By courtesy of Port of Melbourne Authority, Victoria Dock at Port Melbourne was opened for mooring space and yachts were delivered several at a time to Sandringham Yacht Club for safety inspections. Long before the race start, there were some yachts which were lifted from the water for some work at different yacht clubs nearby. This made it difficult for us to know what each yacht was doing. However, shortly before the start, most of the yachts gathered at Victoria Dock and the race atmosphere began to build up steadily.

The participating yachts were divided into the Cruising Division with a heavier displacement and Racing Division for the lighter boats. Since it takes considerable expense and work to measure actual displacement, the value in the entry form was recognized as formal. Only when the value was in question, was displacement measured by the Race Committee. For the yachts whose displacement was on the border line between Cruising and Racing Division, even a small difference in their displacement could change their allocation. So, several yachts finished up changing their division from the one at the time of entry. There were also some teams that lifted their own yachts to make an actual measurement so as to check the proper division. According to the IOR rules, yachts are required to carry a first aid kit but the rules do not specify what drugs should be carried. The Australian regulations specify the sorts and quantities of medicines including morphine for injection as a pain killer. Needless to say, this type of drug is under strict control in Australia but in Japan where there is an especially strict control on it, some concern was expressed by Japanese participants about carrying such a drug. Still, since it is a requirement approved under the Australian law, it was decided to purchase morphine under proper procedures, provided that it would be handed over to the customs officers at their arrival in Japan. Participating yachts were to arrive at Sandringham Yacht Club at least one week prior to the start and undergo the safety inspection in turn. By the day before the start, 64 yachts had passed the inspection.

Start of the First Leg

The strong wind which had started the night before gradually calmed and by the starting time of 1000 hours (EST) on March 21, 1987, it was cloudy with a few drops of rain now and then and a wind speed of 6 to 7 meters per second. At the pier close to the start line, a brass band was entertaining the spectators. On the water, a large number of boats including the Lord Mayor’s yacht were out to see the yachts departing for a distant goal in the Northern hemisphere. Excluding a few yachts that could not get ready in time, 61 yachts made the start and headed straight for Rye on the course set along the coastal line so that they could be seen from land. The first yacht to cross the finish line on this leg was “Cast-away Fiji” but she did not clear the designated start line and was later dis-qualified. There was one recalled yacht and the race result was 23 finishers within the time limit and 2 disqualifications. The yachts then anchored in front of Blairgowrie Yacht Squadron which is located west of Rye Pier. In the evening, a party started at the clubhouse. However, because a protest was lodged against “Bengal Ill ” that won Class A and the decision was to be made on the following day, the award ceremony for the First Leg was not held and the award plaques were to be presented in Osaka.

Start of the Second or Main Leg

The Second Leg or the main course of the race stretching some .5,500 nautical miles (10,200km) from Portsea to Osaka. The starting time for this leg was set at 1300 hours (EST) of March 22, 1987, taking into condiseration the current at the heads of Port Phillip Bay. As on the previous day, the yachts were blessed with light, yet at times a little chilly, rain accompanied by a wind of 7 to 8 meters. Yachts crossed the start line with sails somewhat reefed and started on the long journey to Osaka. As Portsea is a small town away from Melbourne, the number of spectator yachts was smaller than those on the day before. Still, almost 100 boats saw the race yachts off and 9 media helicopters flew overhead. Soon after the start, “SDC Nakiri Daio” came out on top and “Castaway Fiji” was sailing side-by-side. These two yachts left the others behind and passed through the Heads into the Bass Strait. Among the yachts that started on the previous day, there were several yachts not ready for the Second Leg start either because they needed maintenance for the long passage, or because they’d developed new troubles. As a result, 58 yachts made their start at the scheduled starting time. The yachts that were delayed were allowed to start within one week but some started a few hours after the official start while others took off by the next day.

Retirement

Bass Strait, which the yachts face after leaving Port Phillip Bay, is infamous for strong westerly winds. In fact, several yachts were damaged there during the delivery cruise to Melbourne before the race and a yacht dismasted and had to give up the race altogether. Fortunately when race actually started, the wind was weakening. As the yachts were able to sail running with the westerly winds, no yacht retired even in this infamous Bass Strait. However, when the yachts went around from the south to the east coast of Australia, a low pressure front approached and the wind became stronger.

On March 27, “Kobe-Gaufres” dismasted, retired and headed for Sydney. She was followed by a number of other retiring yachts. On March 30, eight yachts retired from the race. One of these yachts dismasted because the chain plate on the side stay loosened but after entering Sydney, a new mast was hoisted and she reached Osaka in the end. In accordance with the rules however, this yacht was disqualified. Except for one yacht that retired due to the personal reason of the crew, most retirements came down to malfunction of gear. Some of the yachts that completed the course were hit with various types of gear problem that they could manage. If it is major damage such as dismasting, there is no way but it should be possible to handle various minor troubles en route. In recent years, perhaps due to the trend of building yachts of lighter displacement, the number or retirements during races is increasing. In this race, 18 yachts retired, amounting to a quarter of the 64 yachts that started.

The Accident of “Castaway Fiji”

“Castaway Fiji” had been competing with “SDC Nakiri Daio” for the top position since the start. On April 2, however, her keel suddenly fell off and she capsized. By all accounts, she sunk on the following day. The skipper, Digby Taylor, was rescued by a following competitor, but the crew, Colin Akhurst, is still missing. Based on Taylor’s report and the radio communication at the time of the accident, we have the following outline. – Around 0100 (AEST)hours on April 2 while Taylor was sleeping in the cabin, the yacht suddenly overturned and soon went upside-down completely. Taylor escaped from the cabin and came up to the surface. Although he could not see Akhurst, they were shouting to each other for a while. However after a half hour or so, they lost contact. As for the keel, only a small portion at the root was left. As the boat was rocked by waves, the mast broke and the yacht began to right itself again. Waves were washing over the deck. Back on the yacht, Taylor ripped off the ARGOS transmitter and operated it. The emergency signal was received by the satellite at 0321 hours at the position 18.375 S, 156.747 E. After analyzing the data from the satellite, the emergency reached the Race Committee at 0614 hours.

Since there are no reefs in the area of the accident indicated by ARGOS, it is unlikely that the yacht’s keel hit a reef and broke. Taylor threw a life ring and the ARGOS transmitter downwind for Akhurst, and kept one life ring for himself. Shortly before dawn, he managed to reach the emergency position indicating radio beacon (EPIRB), and put it into operation. This signal was received by an aircraft flying over the area at 1022 hours and again the fact that “Castaway Fiji” was in distress was confirmed. Since the life raft was located in the front part of the cabin, Taylor gave up the idea of reaching it by diving into the cabin and he kept himself afloat close to the yacht.

The “Castaway Fiji” accident happened in the area between Australia and New Caledonia. French Navy aircraft proceeded to the area and sighted the drifting yacht. They dropped a life raft and confirmed one person swimming to it and getting into it. Taylor soon fell asleep due to exhaustion. In the meantime, a request for search for “Castaway Fiji” was sent by radio to the race fleet. Five yachts responded and headed for the site. “Kirribilli”, the top boat in Class B, received this request for search about 140 nautical miles from the site. At around 2000 hours, she sighted a drifting life raft with a small light and rescued Taylor. Also, Malaysia’s 30, 000-ton bulk cargo ship “Bunga Kesidang” arrived on the scene to join the search and Taylor was transferred from “Kirribilli” to “Bunga Kesidang”. “Kirribilli” then returned to the race. Following this, French Navy planes, Royal Australian Air Force planes took over the search for the missing Akhurst but since no sign at all could be found even by the evening of the following April 3, the search was scaled down. “Bunga Kesidang” also continued the search for about 30 hours with Taylor on board and then returned to her original course. She then stopped at Rabaul, where Taylor went ashore.

The five yachts that cooperated in the rescue operations were “Kirribilli”, “Sitka,” “Sunchaser,” “Devona” and “Sir Isaac.” Judging from the courses taken, rescue operations of “Devona” and “Sir Isaac” did not seem unfavorable for racing, and so the time compensation was not considered. This was partly due to the fact that there was no regress requested from them. For the other three yachts, time compensation was given to their elapsed time. Also, the crew members of “Kirribil-li” who rescued Taylor were awarded with words of appreciation and a memento by the Ambassador of New Zealand at the prize awarding ceremony in Osaka.

Finish

When you approach Japan, particularly from Kii Suido to Osaka Bay, marine traffic increases considerably. This area must have kept the crew members on alter since they did not see other vessels at all up to that point. Around the finish line that was set just outside of Port of Osaka’s harbor limit, often there were ships anchoring during the night. Also the shore lights made it difficult to find the finish line form the south and escort boats were sent to guide the race yachts to the finish line. When the yachts neared the finish line, the ARGOS data was no longer useful due to the time lag for data processing and we had to rely on direct radio communication to keep in contact. However, perhaps because crew members were exhausted over a long passage, radio communication did not go smoothly in many cases and it often took a great deal of time and effort for the nighttime escort boats to find the race yachts. The frequent changes in wind direction in Osaka Bay also made it difficult for us to confirm yacht’s movements. At 0706 hours on April 23 (JST), “SDC Nakiri Daio” finished first within 32 days which was earlier than we expected. She was welcomed by fireworks and water sprays from firefighting boats. This first arrival was followed by a series of finishing yachts. On one day, we even had as many as five finishing yachts. In oe instance, two yachts sailed together at distance they could recognize one another by sight since Kii Suido ; a yacht which was over-taken after entering Osaka Bay ; and two yachts that finished in two minutes apart after sailing for more than one month. Just one month after the first boat finished, the last yacht finished bringing the race to an end. It was the 62nd day since the start, taking twice as long as the time the first yacht recorded. However, there was still nearly three weeks left before the time limit was up.

Race Courses Sailed

In this race, there were no restrictions on “selecting courses” and it was a big question as to which course they would take among islands east of New Guinea. There were three possible courses : the eastern course to pass the Solomon Islands to port ; the central course between New Hebrides and New Britain ; and the western course between New Britain and New Guinea. When it comes to distance, the central course is the shortest, but the northern part of these islands falls between the trade wind zones which exist to the north and south of the equator. There, both wind direction and wind velocity are not stable as in the trade wind zone.

When we look at the course that each yacht took, we find that 10 yachts took the eastern course, 35 yachts took the central course and 1 yacht took the western course. Most yachts took the shortest course based on common sense. Among the yachts that took the eastern course were the heavier yachts. When we look at the statistics on wind, it appears that the eastern course could provide somewhat better winds. Thus, heavier yachts might have taken the eastern course in the hope of a better wind. “SDC Nakiri Daio” was the first to cross the equator, almost halfway on the course, on the evening on April 8, and “Alstar” and “Dr. Rai” followed in the morning of April 10.

After the equator, we did not see a big change of the order of the fleet and this meant there was no course that was extremely favorable compared with others. The Kuroshio (Japan Current) flows east-west direction to the south of Japan. As winds become weaker as they approach Japan, it seems favorable for the yachts to sail across Kuroshio to the north at the west of Kii Suido. However, perhaps because Kuroshio has moved away from Japan to the south currently due to cold water, apparently there was no yacht that was pushed away by Kuro-shio and had difficulties in entering Kii Suido. In fact, the greatest difficulty for the yacht near Japan was the current at Yura Seto.

Across the Finish Line

At 07:06:26 on April 23, 1987, “SDC Nakiri Daio” crossed the finish line’ in Hokko Yacht Harbor. Welcomed by media helicopters, spectator boats and 1,000 people on the shore, she had made the voyage in 31 days 19 hours 6 minutes and 26 seconds. In the early morning of the following April 24, “Dr. Rai” finished and then early on the 25th, “Al-star” crossed the finish line. At the finish, every crew looked bright with confidence and relief, whatever their placing was. At 04:17:52 of May 23, 1987, “Boris B” made the last finish on a rainy and windy day and brought an end to the race of 62 days. Yachts completing the course were 46 and 18 retired.

Images from the 1987 Record Book

Click to enlarge